- Home

- Heather Mackey

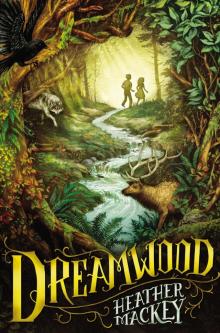

Dreamwood

Dreamwood Read online

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

Copyright © 2014 by Heather Mackey.

Illustrations copyright © 2014 by Teagan White.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mackey, Heather.

Dreamwood / Heather Mackey.

pages cm

Summary: “12-year-old Lucy Darrington goes on a quest to find her missing father in a remote, magical territory in the Pacific Northwest”—Provided by publisher.

[1. Supernatural—Fiction. 2. Adventure and adventurers—Fiction. 3. Missing persons—Fiction. 4. Forests and forestry—Fiction. 5. Runaways—Fiction. 6. Northwest, Pacific—History—19th century—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.M198636Dre 2014

[Fic]—dc23

2013039402

ISBN 978-0-698-15862-7

Version_1

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Acknowledgments

For my mother and father

Ever since the lumberjacks boarded the train, Lucy Darrington had been watching them, wondering when they’d make trouble.

It was late afternoon, and she was sweaty in her blue wool school dress. Crabby, too. Her fingers itched inside her gloves, her petticoat was heavy as a wet mattress, and her toes were falling asleep inside her stiff lace-up boots. Since running away from the Miss Bentley’s School for Young Ladies in San Francisco, she’d spent four days on this train and felt like she couldn’t take another minute. She’d been staring out the window at the endless northern forests when the lumberjacks boarded—three men in shirtsleeves and suspenders—stomping in like elephants and taking up about as much space. Their legs splayed into the aisle amid a growing cluster of empty amber bottles. Right away they started drinking and farting and telling one another stories that made her shudder even as she crept two rows closer to hear them better.

Now one was telling the others about a friend who’d been awakened one night by strange noises. “He gets up and looks out his door. In front of his barn he sees a terrible shadow. A monster.”

“What did it look like, Bert?” one asked. He was younger than the other two, with thick blond hair and a simple face.

Bert, the biggest of the three, peered slyly at the other two and dropped his voice. “Big. Ragged and feathery. Like a wolf crow.”

A wolf crow. They were silent, the better to think about such a beast. “So what happened?” asked the third man, sour faced under a wiry black beard.

“He goes outside. Suddenly behind him he hears the monster’s terrible screams and snorts. He turns, and there’s the wolf crow coming straight for him. And right before it reaches him . . .”

Bert took a deep breath. His chin quivered as if he were trying to hold in some terrible truth. Lucy leaned forward, listening hard. And then it came: a belch so loud her ears rang.

The other two groaned.

“Come on, Bert, what happened?”

“Was it the wolf crow, Bert?”

Bert leaned back, pleased. “Naw. He fainted is all. When he wakes up there’s his pig standing over him—with a chicken on its head. Dang thing had gotten out of the barn.”

A chicken riding a pig!

They pounded on the seats, this was so good. Lucy thought the wooden slats of the benches might break.

More burps, farts. Bert stroked his beard—his was the sort that shot out in all directions: a frozen explosion of hair. The train shuddered and clacked; outside the forest went by unendingly.

Lucy fell back in her seat—she’d have to remember that one. Imagine being scared of a chicken riding a pig.

Pity she had no one to tell the story to. She had no friends from her time at Miss Bentley’s; she was poor, and her father was eccentric. The girls had been a bunch of sheep who cared only about stockings and hair ribbons. No one had been interested in science, and certainly not in ghostology, which is where she intended to make her name one day—even if her father thought she should enter a field with a more promising future.

Ghost clearers were a dying breed, the profession grown disreputable, even mocked. In their heyday, they’d helped the country heal after the bloody North-South War, when whole pockets of land were overrun by angry spirits. But that was forty years ago; the country had been consumed by grief, giving ghosts the energy they liked to attach themselves to. It was a new century now, and ghosts, which were sensitive to electricity, were disappearing as more places used electrical lights. Ghosts had become an unfashionable problem most people would not admit to having.

Her old friends—a gang of ragtag children she’d played pirates and forts with—were thousands of miles away in Wickham, Massachusetts, the little town outside of Boston where she’d grown up. Her father hadn’t said it at the time, but from the way they’d left—quick in the dead of night, barely ahead of the debt collectors—she doubted she’d ever see the place again.

She missed their comfortable house in Wickham, the basement laboratory where her father conducted his research into the unseen world of spirits, she sitting at his elbow, jumping up to assist when needed. The scandal that cost him his job destroyed their old life permanently.

But, there was no sense regretting the past. “Onward, eh, Lucy?” he would say, readying his ghost-clearing bag. She could picture him fastening his high collar and ascot—he always looked proper, no matter how low their fortunes sank—his blue eyes twinkling in a conspiracy he shared only with her.

Onward, she thought dully, pressing her nose against the window.

Was the train slowing? The scenery outside hadn’t changed; there was the thick, unvarying forest and a distant band of blue on the horizon that marked the Pacific Ocean. Still no signs of any town or settlement. But maybe they were coming up on Pentland. Lucy unlatched the window and stuck her head out, risking cinders from the whirling smoke. She squinted up at the steam engine, puffing along. They were definitely losing speed.

She sat back down and brought out her map. Everything a hundred miles north of San Francisco was green, First Peoples’s Federation territory. Here and there were small orange blobs, marking outposts of the American States. Saarthe, a mitten-shaped peninsula that stuck out from the coast like a hand g

rabbing at the ocean, was one of these. Pentland, its capital, was where her father had gone nearly six months ago, and where the train was due to arrive that evening.

If she survived that long without exploding from impatience. From the small black case on the seat beside her came the low ticking of mechanical workings. But none of the instruments inside it was a watch. She debated whether to ask the lumberjacks for the time. Bert had just started a new story. This one was about a man who’d gone into his shed to get what he thought was an empty sack.

“Only he picks it up, and it’s really heavy. So he thinks, I’m just gonna put my hand in there . . .”

He went silent, and Lucy readied herself for another operatic belch. But the burp she expected didn’t come. With a squeal of brakes and a puff of steam, the train stopped.

Quiet descended on the railcar, the three lumberjacks staring gloomily at something on their side of the train. The only sound was the vibration of the devices in her black case.

That was odd. They never reacted unless there was a strong energy source around.

She couldn’t see anything from her window, so Lucy crossed the aisle to look out on the other side of the train.

Now she understood why the lumberjacks were quiet.

Just outside the train a cluster of thick wooden poles rose into the sky, standing like guardians of the dark and brooding forest behind them. They were carved and painted with faces—unsettling combinations of animal and human—and their eyes stared fiercely ahead.

Why are you here? the poles seemed to ask. Explain yourself.

The door to the car opened, the young red-haired porter holding it solemnly as if attending someone of great importance. A girl walked in, the cape of gray fur about her shoulders not quite concealing the quiver and bow on her back.

Lucy had seen First Peoples before, of course. Back in Wickham she’d seen Wampanoag along the deer path in the woods behind their house, collecting chestnuts in the autumn or at the market, selling deerskin shirts and gloves. Several of them would come and talk to her father, staying late into the night. They’d been kind and joking; some who visited year after year were like family.

This girl was different.

She held herself like a queen, not deigning to look at either the lumberjacks or Lucy. The ruddy, freckle-faced porter bowed his head as she stepped past him.

Her shiny black hair was woven with beads and charms and something soft and glowing: gold. She had gold, too, in her ears, around her neck, and around her wrists.

One of the lumberjacks muttered something under his breath. On their way west, Lucy and her father had landed in a few places where there was prejudice, hatred even, between First Peoples and settlers. And she knew that decades ago, parts of the northwest had been consumed in bloody fights for territory. The Lupines, the most powerful people in the region, had managed to hold vast tracts of forest . . . maybe to the resentment of the surviving settlers. She’d heard something in one of the stations they’d stopped at yesterday about a problem with Saarthe’s timber and settlers being out of work.

The door closed, and with a whine of relief, the train began to move again.

To get to the empty seats at the back, the girl would have to walk by the lumberjacks at the front. Bottles and other trash were littered about the aisle by their feet—an obstacle course. The men watched silently, sullenly as the girl balanced herself while the train swayed and shook.

She took light, graceful steps, avoiding the mess.

And then there was a jolt.

A foot came down wrong, and a beer bottle went fizzing on the floor. One of the men cursed. “Look at that!”

Bert, closest to the girl, stood up and reached out a powerful arm. He towered over her, and as the train shuddered it looked like he pushed her.

“Don’t do that!” Lucy said, rising from her seat and bursting into the aisle, black case in hand. It had sharp corners, and she could bring it down on someone’s knee if she had to.

The lumberjacks turned to her in surprise, and Lucy realized they’d forgotten she was even there. In their beer-soaked brains they were probably struggling to account for this small, fierce creature who’d come out of nowhere to challenge them. She was halfway past twelve and any day would have a growth spurt. But for now, people—especially dim-witted ones—looked at Lucy and saw only a child.

A sweet, milk-faced child, with unruly curls of hair like a cherub’s. Lucy watched as they registered her appearance. The teachers at Miss Bentley’s always complained that she was desperate for attention—they couldn’t understand it. Why wouldn’t she simply be quiet and do as told, especially when she looked (well, except for that hair) like a nice, docile girl: cornflowerblue eyes, a small chin, and delicate blond eyebrows arched like a china doll’s. But Lucy didn’t want the attention such girls got—pats on the head and an opportunity to bring chalk to the teachers. She wanted to make a mark on the world—and you couldn’t do that by fading into the background.

“What? Bother her? No! I was trying to help her was all.” Bert’s blocky face fell. Rather unnecessarily (for the First Peoples girl had regained her balance) he still held out one meaty forearm to her. “I didn’t mean anything. Honest.”

“My friend’s got terrible manners,” the blond one said, bowing his head as the girl looked down on him. “We’re sorry this mess got on your boots.”

It took Lucy a moment to catch up. They hadn’t meant to bother her; instead, they were frightened they’d offended her.

Embarrassed, Lucy slunk back into her seat. “My boots have seen worse than your beer, settlers,” the First Peoples girl said in a raspy, accented voice. “No harm is done.”

Then she made her way down the aisle and slid into the seat facing Lucy’s.

An awkward silence ensued; at least it was awkward for Lucy, who tried not to stare at her new companion. The girl had a finely sculpted face, delicate ears, and lovely dark eyes. She was sleek and composed and taut as a bowstring even when sitting. The fur she wore was a black-tipped gray, rough and bristly. It occurred to Lucy that it wasn’t rabbit or anything soft, but the fur of a predator . . . a wolf, perhaps.

“Is that a weapon?” the girl asked, eyeing Lucy’s black instrument case. It had been vibrating ever since they’d seen those frightening poles. But in the excitement of the last few minutes Lucy had forgotten all about it.

“This? No. I just thought I could wallop somebody with it.” Lucy watched it shake. “I’ve never seen it act like this, though.” Frowning, she unlatched the case and opened the lid. A brass disc flipped out of its position in the velvet drawer, like a fish. Lucy forced it back into place and shut the lid.

“What is it?” The girl leaned back, her glossy black brows drawn together in suspicion. “Does it explode?”

“No!” Lucy thought this was funny. “It’s just a vitometer. It won’t hurt you. In fact, it almost never moves. My father invented it. He’s invented a lot of things.” She couldn’t seem to stop herself from running on—it had been days since she’d seen a girl close to her own age—and only now did Lucy realize how lonely she’d been. “He’s been living in Pentland and I’m going up to live with him.” She had his letter, thinned from the many times she’d unfolded and folded it again, safely in her pocket even though by this point she knew it by heart:

I’m on the verge of a breakthrough. Though I don’t know how I’ll manage without my trusted assistant.

“Oh.” The girl received this information coolly; she was busy rearranging her fur. “Is he a tree cutter?”

“No, he’s a . . .” And here was where Lucy ran into difficulty. Not long ago, she would have proudly called her father a ghostologist. But the girls at Miss Bentley’s had made it clear this was a ridiculous profession. Even now with the school hundreds of miles behind her, Lucy still felt hurt: They’d wanted to hear her stories, and then they�

��d acted as if her father was no better than a rat catcher.

“He’s a scientist,” Lucy said, lifting her chin. He was! You had to know an awful lot about energy and physics—psychology, too—if you were going to hope to understand ghosts. And there was more to their study than just knowing how to clear them. One day Lucy could see herself touring the country giving ghostology demonstrations, rather like her idol, the glamorous paleontologist Irene Zerinka, who packed lecture halls and was rumored to require ten railcars just to transport her dinosaur skeletons.

The girl smiled and Lucy gathered she liked this answer better than tree cutter.

“I am Niwa Sillamook,” she said. Her eyes flickered with defiance, as if she expected Lucy to react to her name—and not in a good way.

But to Lucy the name meant nothing, and she already admired the girl’s poise and self-possession. “Lucy Darrington,” she replied eagerly, reaching out a hand to shake. But the girl raised her palm up, fingers spread. And after a moment, Lucy stripped off one glove and did the same. Their palms touched. Niwa’s hand was warm, with a ridge of callus.

The touch seemed to melt any remaining awkwardness between them. Niwa leaned forward and confided, “I am meeting my father, too. I would travel on foot, but he is impatient.”

“You’d travel by yourself on foot? Through the forest?” The girl was maybe sixteen, but Lucy thought even an adult might not want to travel in such a wild, untamed place. Her father had never been much of an outdoorsman. And although they’d traveled many places it had usually been by train. They’d never camped.

Niwa seemed amused to be the object of so much awe and admiration. “You travel by yourself,” she pointed out. “On a train.”

Lucy regarded the jostling, jerking railcar. At the front, the lumberjacks had begun to smoke, and a noxious, gray, tobacco-scented cloud rose in the stale air.

She’d been on many trains since leaving Wickham. Her sojourn at Miss Bentley’s had been the first time she’d been in one place more than three months at a time. Before that had been New Orleans, where the local voodoo doctors hadn’t been very happy to have a ghost clearer from Massachusetts horn in on their business. And before that they’d been in Nebraska, her father somehow running afoul of the snake-handling tent preachers that crisscrossed the prairie.

Dreamwood

Dreamwood